What is a Bond? Financial concept and pricing mechanisms explained

Explore bonds in finance: Learn about types, examples, and pricing mechanisms, demystifying this financial concept.

What exactly is a Bond?

A bond functions as a fixed-income security, symbolizing a loan provided by an investor to a borrower, commonly corporations or governments. It acts as an agreement, detailing the terms of the loan and its repayment. Bonds are employed by various entities to fund initiatives and activities, with bondholders serving as creditors of the issuer. Key details of bonds encompass the maturity date for principal repayment and the terms governing interest payments, which can be fixed or variable.

Here are the main points to remember:

- Bonds represent corporate debt that companies issue and transform into tradable assets.

- Bonds are known as fixed-income instruments because they historically provided a fixed interest rate (coupon) to investors.

- Variable or floating interest rates are also prevalent in modern bonds.

- Bond prices move in the opposite direction to interest rates: when rates rise, bond prices decline, and vice versa.

- Bonds have maturity dates, after which the issuer must repay the full principal amount, or risk default.

Who are the Issuers of Bonds?

Bonds, serving as debt instruments, are utilized by governments and corporations for borrowing purposes. Governments require funds for various projects such as infrastructure development or in times of unexpected expenses like war. Similarly, corporations borrow to expand their operations, invest in assets, undertake projects, conduct research, or hire staff. However, these entities often require substantial amounts of capital beyond what traditional banks can provide.

Bonds offer a solution by enabling numerous individual investors to act as lenders. Through public debt markets, thousands of investors can collectively provide the required capital. Furthermore, these markets allow for the buying and selling of bonds among investors, even after the initial issuance, providing flexibility and liquidity in the bond market.

Understanding the Mechanisms of Bonds

Bonds, often known as fixed-income securities, represent a significant asset class familiar to individual investors, alongside stocks and cash equivalents. When organizations require funding for various purposes, such as new ventures or ongoing operations, they may issue bonds directly to investors. These bonds outline the loan terms, including interest payments and the maturity date when the principal must be repaid. The interest rate, known as the coupon rate, determines the payment. Initially priced at par, usually $1,000 per bond, the market price fluctuates based on factors like issuer credit quality, time to maturity, and prevailing interest rates. Bondholders can sell their bonds to other investors, and borrowers may repurchase bonds if interest rates decrease or their credit improves.

Key Features of Bonds

Most bonds have several fundamental features in common:

- Coupon dates: These are the dates when interest payments are made. While payments can occur at any interval, semiannual payments are standard.

- Face value (par value): This is the amount the bond will be worth at maturity and is used to calculate interest payments. For instance, if an investor buys a bond at a premium of $1,090, or at a discount for $980, they will still receive the face value of $1,000 when the bond matures.

- Coupon rate: This is the interest rate the issuer pays on the face value of the bond, usually expressed as a percentage. For example, a 5% coupon rate means bondholders receive $50 annually for a bond with a face value of $1,000.

- Issue price: This is the price at which the bonds are initially sold by the issuer, often at par value.

- Maturity date: This is the date when the bond matures, and the issuer repays the face value to the bondholder.

Two primary factors affecting a bond's coupon rate are its credit quality and time to maturity. Bonds issued by entities with lower credit ratings tend to offer higher interest rates to compensate for the increased risk of default. Similarly, bonds with longer maturity periods typically carry higher interest rates due to the heightened exposure to interest rate and inflation risks over an extended duration.

Credit ratings for bonds are determined by credit rating agencies such as Standard and Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch Ratings. Bonds with the highest credit quality, known as "investment grade," include those issued by stable entities like the U.S. government and reputable companies.

Bonds that fall below the investment-grade threshold but are not in default are termed "high yield" or "junk" bonds. These bonds offer higher coupon payments to investors as they carry a greater risk of default in the future.

The value of bonds and bond portfolios fluctuates with changes in interest rates, a measure referred to as "duration." It's essential to note that duration does not indicate the time until a bond matures but rather the bond's sensitivity to interest rate shifts. The rate of change of this sensitivity is known as "convexity," which requires complex analysis typically conducted by financial professionals.

Types of Bonds

Bonds are typically categorized into four main groups traded in the markets. However, on certain platforms, you may also encounter foreign bonds issued by global entities.

- Government bonds include those from the U.S. Treasury, categorized based on maturity: Bills (under a year), Notes (one to 10 years), and Bonds (over 10 years). Collectively, they are referred to as "treasuries." Bonds from national governments may be termed sovereign debt.

- Corporate bonds originate from companies, which choose this financing route over bank loans due to more favorable terms and lower interest rates often available in bond markets.

- Municipal bonds stem from states and municipalities, with some offering tax-free coupon income for investors..

- Agency bonds come from government-related entities like Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac.

Varieties of Bonds

- Callable Bonds: Issuers can redeem these bonds before maturity, typically when interest rates decline, posing higher risks for bondholders.

- Zero-Coupon Bonds: These bonds don't pay periodic interest but are sold at a discount to their face value, providing a return upon maturity.

- Convertible Bonds: These instruments allow bondholders to convert their debt into stock based on certain conditions, such as share price.

- Puttable Bonds: Bondholders can sell these back to the issuer before maturity, offering protection against potential value declines or rising interest rates. These bond types, each with unique characteristics, play roles in various investment strategies. Bonds are priced based on market demand, with their values fluctuating in response to interest rate changes.

Pricing mechanisms of Bonds

The prices of bonds are influenced by their unique characteristics and fluctuate daily, similar to other publicly traded securities. Supply and demand dynamics dictate these changes. While bonds are typically discussed with the assumption of being held until maturity, they can be sold in the open market at any time, leading to potential dramatic fluctuations in their prices.

Changes in interest rates in the economy prompt fluctuations in the price of a bond. This is due to the fixed-rate nature of bonds, where the issuer commits to paying a coupon based on the bond's face value. For instance, with a $1,000 par value and a 10% annual coupon rate, the issuer disburses $100 annually to the bondholder.

Initially, if prevailing interest rates match the bond's coupon rate, say 10%, an investor would be indifferent between investing in the corporate bond and a government bond, both yielding $100. However, if interest rates subsequently decrease to 5% due to economic downturn, the government bond's return diminishes to $50, while the corporate bond still offers $100, thereby influencing investor decisions.

This discrepancy renders the corporate bond significantly more appealing. Consequently, market investors will increase their bids for the bond until its price aligns with the prevailing interest rate environment. For instance, in this scenario, the bond would trade at a premium of $2,000, ensuring that the $100 coupon represents a 5% yield. Conversely, if interest rates surged to 15%, an investor could earn $150 from the government bond, making the $100 return from the corporate bond less enticing. Consequently, the bond would be sold until its price adjusted to equalize the yields, reaching a price of $666.67 in this case.

Relationship between Bond prices and interest rates

This is the rationale behind the widely known statement that bond prices move inversely to interest rates. As interest rates increase, bond prices decrease to align the bond's interest rate with the prevailing rates, and vice versa.

Another way to illustrate this concept is by examining the yield on the bond following a price change, rather than an interest rate change. For instance, if the price declines from $1,000 to $800, the yield increases to 12.5%. This occurs because you receive the same guaranteed $100 on an asset valued at $800 ($100/$800). Conversely, if the bond's price rises to $1,200, the yield diminishes to 8.33% ($100/$1,200).

Yield-to-Maturity (YTM)

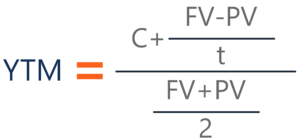

The yield-to-maturity (YTM) of a bond provides another perspective on its price. YTM represents the total anticipated return on a bond if it is held until maturity. It is regarded as a long-term bond yield, expressed as an annual rate. Essentially, YTM signifies the internal rate of return of an investment in a bond under the assumption that the bond is held until maturity and all payments are made as scheduled.

While YTM involves a complex calculation, it serves as a valuable concept for assessing the attractiveness of one bond compared to others with varying coupons and maturities in the market.

Another metric used to gauge the expected fluctuations in bond prices due to interest rate changes is called the duration of a bond. Initially tied to zero-coupon bonds, duration is typically measured in years, reflecting the bond's maturity.

However, for practical purposes, duration is interpreted as the percentage change in a bond's price in response to a 1% shift in interest rates. This practical interpretation is referred to as the modified duration of a bond.

Calculating duration allows for the assessment of a single bond's or a portfolio's sensitivity to interest rate adjustments. Generally, bonds with longer maturities and lower coupon rates exhibit higher sensitivity to interest rate fluctuations. It's important to note that a bond's duration is not a linear risk measure; it changes as prices and rates fluctuate, and convexity is used to analyze this relationship.

Illustrative Bond Scenario

A bond signifies an agreement wherein a borrower commits to repaying a lender the principal sum along with typically accruing interest on a loan. Bonds are issued by various entities such as governments, municipalities, and corporations. The interest rate (referred to as the coupon rate), principal amount, and maturity terms vary across bonds to align with the objectives of both the bond issuer (borrower) and the bond purchaser (lender). Corporate bonds commonly feature options that can influence their value, making comparisons challenging for non-professionals. Bonds can be traded before reaching maturity, with many being publicly listed and available for trading through brokerage services.

While governments predominantly issue bonds, corporate bonds can be acquired through brokerages. If considering this investment, selecting a suitable broker is necessary. One can consult resources like Investopedia's compilation of top online stock brokers to identify brokers aligning with individual needs.

Given that fixed-rate coupon bonds maintain a consistent percentage payout relative to their face value over time, the market value of the bond fluctuates concerning the attractiveness of its coupon vis-à-vis prevailing interest rates.

Consider a bond issued with a 5% coupon rate and a $1,000 par value. Annually, the bondholder receives $50 in interest income (often split semiannually). Assuming a static interest rate environment, the bond's price remains at par value.

However, if interest rates decrease and comparable bonds offer a 4% coupon, the original bond becomes more desirable. Investors seeking higher coupon rates must pay a premium to acquire the bond, driving its price up. Consequently, new investors receive a total yield of 4%, as they purchase the bond above par value.

Conversely, if interest rates rise and similar bonds offer a 6% coupon, the 5% coupon loses appeal. The bond's price depreciates and starts trading at a discount relative to par value until its effective return matches the prevailing 6%.

Understanding the mechanics of Bonds

Bonds are financial instruments issued by governments and corporations to raise capital from investors. For sellers, issuing bonds serves as a means of borrowing money. Conversely, for buyers, purchasing bonds constitutes an investment, as it ensures repayment of principal along with a series of interest payments. Certain bonds may also provide additional advantages, such as the option to convert the bond into shares of the issuing company's stock.

The bond market typically exhibits an inverse relationship with interest rates. When interest rates increase, bonds are often traded at a discount, whereas during periods of declining interest rates, bonds tend to trade at a premium.

An illustration of Bonds

As an example, let's look at XYZ Corporation. XYZ intends to secure $1 million for constructing a new factory, yet traditional bank financing isn't feasible. Consequently, XYZ opts to procure the funds by issuing $1 million worth of bonds to investors. According to the bond's terms, XYZ commits to providing its bondholders with a 5% annual interest rate over a five-year period, with interest payments made semiannually. Each bond holds a face value of $1,000, indicating that XYZ is issuing a total of 1,000 bonds.

What are some different types of Bonds?

The aforementioned illustration pertains to a conventional bond, yet various specialized bond types are available. For instance, zero-coupon bonds forego interest payments throughout the bond's duration. Instead, their par value—what the investor receives at the bond's maturity—is greater than the purchase price.

Convertible bonds, conversely, grant the bondholder the option to convert their bond into shares of the issuing company, subject to specific conditions being met. Numerous other bond variants exist, offering attributes related to tax management, inflation protection, and more.

Is Investing in Bonds Beneficial?

Bonds are generally less volatile than stocks and are commonly recommended as a component of a diversified investment portfolio. As bond prices typically move inversely to interest rates, they often appreciate when interest rates decline. Holding bonds until maturity ensures the return of the full principal amount along with the accrued interest payments over time. This characteristic makes bonds appealing to investors seeking income while aiming to preserve capital. Experts often suggest that as individuals age or near retirement, they should gradually increase the proportion of bonds in their investment portfolio.

How to Purchase Bonds?

Although specialized bond brokers exist, nowadays, most online and discount brokers provide access to bond markets, enabling you to purchase bonds similar to how you would buy stocks. Treasury bonds and TIPS are usually sold directly by the federal government through its TreasuryDirect website. Alternatively, you can indirectly invest in bonds through fixed-income ETFs or mutual funds, which hold portfolios of bonds.